Layer

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

An anamorphic hidden painting of Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788). At first glance the object appears to be a smear of oil paints on a black wooden board, but when paired with a mirrored cylinder, the true nature of this unique object is revealed. Prince Charlie is reflected right back at you! Discovered by chance in a London junk shop in 1924 and purchased for £8 by the museum’s founder, Victor Hodgson, it has been a star object in our collection ever since. In the 18th century it was treasonable to support the exiled Stuart dynasty, so their supporters known as Jacobites, devised ways to secretly display their loyalty. They developed an elaborate series of codes and symbols to hide their allegiances from the ruling Hanoverian regime. This is one of the most unusual examples of Jacobite material culture. The portrait would have been used to drink toasts to the exiled Prince. If a non-Jacobite came into the room, the cylinder could be whisked away and allegiances hidden. The Secret Portrait featured in the West Highland Museum’s “Prince Charles Edward and the ’45 Campaign” exhibition, 1925.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

A copper printing plate commissioned by Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788) in 1746. Designed and etched by the artist Robert Strange (1721 -1792), the plate is completely unique and was intended to be used to print bank notes during the 1745 Rising, but was never used. When the Jacobite army was defeated at the Battle of Culloden, the army fled and the plate was found abandoned at Loch Laggan. It was presented to Clan MacPherson and remained in their care until the museum purchased it in 1928. The object featured in the West Highland Museum’s “Prince Charles Edward and the ’45 Campaign” exhibition, 1925.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

Print made by the prominent Scottish artist and etcher Sir D Y Cameron (1865 -1945). In 1928 The Strange Plate came into the museum’s collection, a copper plate made in 1746 and intended to print bank notes for the Jacobite cause. Cameron, was one of the earliest supporters of the museum which was founded in 1922. As one of the foremost printers of his day, he printed 57 signed proofs from the plate and these were sold for 10/6 to raise funds for the museum. Prints sold at auction in 2019 and 2020 made £875 and £1,625 respectively. The object featured in the West Highland Museum’s “Prince Charles Edward and the ’45 Campaign” exhibition, 1925.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

Metal knife blade with no handle. Although the knife is poorly constructed and rusting its important because it was purportedly found on Drumossie Moor near Inverness. This was the site of the Battle of Culloden, the last engagement of the 1745 Rising. Interestingly, it was loaned to the museum in 1925 for the “Prince Charles Edward and the ’45 Campaign” exhibition by Mrs A. Mansfield-Forbes, a close friend of the museum’s founder Victor Hodgson. It was never reclaimed by its owner and has remained in our care ever since. However, in 2019, Mrs Mansfield-Forbes’ great grandson contacted the museum after he found a loans form and correspondence relating to the loan while researching his genealogy. The knife was officially gifted to the museum in 2019 along with copies of correspondence from the original lender.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

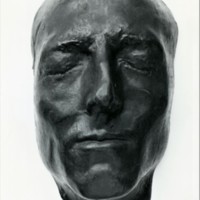

Prince Charles Edward Stuart's (1720 - 1788) death mask. Thought to be a copy of an original made by Barnar dina Lucchesi, one of a family of modellers in Rome. brought this mask to Scotland in 1839. The mask had been handed down through his family. Lucchesi settled in Glasgow where he continued to work as a modeller until 1863. Lucchesi fell on hard times and some of his belongings, including the mask, were sold. Eventually the mask ended up being purchased by a sculptor named Ferguson. When it came into Ferguson's possession it was said to have hairs attached adhering to the eyebrows and eyelids! This bronze cast of the death mask was loaned to the museum in 1951 by the Scottish independence campaigner Wendy Wood.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Flora MacDonald's shoe buckles

Description:

A pair of decorative 18th century shoe buckles with paste 'jewels'. Said to have been worn by Flora MacDonald (1722 -1790). Flora was a heroine of the 1745 Jacobite Rising. After two months on the run, Prince Charles Edward Stuart arrived at the island of South Uist where he met 24 year-old Flora. As both her step-father and her fiancée Allan MacDonald were in the Hanoverian army of King George II, she was an unlikely ally. However, she agreed to help the Prince escape from his pursuers by smuggling him away from the island by boat.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

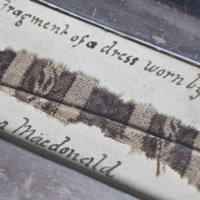

A framed fragment of cloth decorated with brown sprigged stripes on a cream background. It is mounted on a glazed wooden and silver frame. The piece is said to have been from a dress worn by Flora MacDonald (1722 -1790), heroine of the 1745 Rising. Flora helped the Prince escape while he was on the run from the Hanoverian army in 1746. She obtained permission from her step-father, the head of the local militia, to travel from South Uist to the mainland, accompanied by two servants and a crew of six boatmen. Famously, the Prince was disguised as Betty Burke, her Irish maid. Flora quickly became a celebrated heroine of the Rising and relics associated with her became very collectable.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

Bone china fluted handle less tea cup and deep saucer said to have been part of a set that belonged to Flora MacDonald (1722 -1790).

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

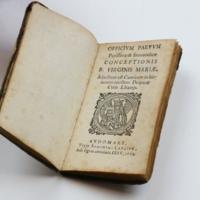

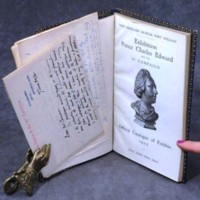

“Little Office of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary” prayer book. Originally bound in plain card it has decorated with an intricate design of woven coloured straw. Published by Joachim Carlier at St Omer Audomari in 1672, the prayer book was one of the most popular devotions of the Roman Catholic laity before the Reformation. The prayer book belonged to Flora MacDonald’s mother and was used by Flora. The straw decoration is rare, the only known examples of similar works of books decorated with woven straw found in the United Kingdom date from a later period and were made by Napoleonic prisoners of war.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

A paper and ivory fan depicting Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788) with the Mars, Roman god of war, and Bellona, Roman goddess of war. They are surrounded by other classical gods. The figures to the right are reputed to be the family of the Hanoverian King George II fleeing. This design is by tradition attributed to Robert Strange, the Jacobite engraver. These fans were said to have been distributed to ladies at a ball at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh in 1745. Prince Charles held the ball to celebrate the Jacobite victory at the Battle of Prestonpans. They are an important example of Jacobite material culture.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

A hard tartan jacket made in Uist. With linen lined sleeves. The colourful tartan lining differs between the skirts and bodice. It is a fantastic example of 18th century textile design. It is said to have been worn at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. The battle on Drummossie Moor outside Inverness, was the last pitched battle to be fought on British soil and the final engagement of the 1745 Rising fought between the Jacobite and Hanovarian armies.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

A circular box with an enamel tartan decoration. The hinged cover opens to expose a plain interior. However, the hidden double lid opens to reveal a finely enamelled portrait of Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788) dressed in a tartan jacket with the orders of the Garter and Thistle decorations, white cockade and blue bonnet. Hidden portrait snuff boxes such as this are amongst the most iconic Jacobite works of art. This example is in particularly good condition and finely enamelled. The portrait is a variant of the famous Robert Strange example which likely date this piece to circa 1750. Purchased in 2019 with the assistance of the Art Fund and National Fund for Acquisitions.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

A fine example of a mid-18th century drinking glass with an air twist stem, engraved with Jacobite symbols. Drinking toasts to the exiled Stuart dynasty was an important part of Jacobite secret culture. Jacobites would often pass their glass over a water bowl to toast their “King across the water”. Another popular toast was “to the little gentleman in the black velvet waistcoat,” which was a reference to William of Orange’s horse tripping over a mole hill. The fall caused him to break his collar bone and he subsequently died when he contracted pneumonia. The Jacobite symbols engraved on this glass are typical. The six-pointed star represents royalty. A rose signifies James VIII (II of England, 1688 - 1766) and buds represent Prince Charles Edward (1720 - 1788) and his younger brother, Prince Henry Benedict (1725 – 1807). The motto “Fiat” translates as “Let it be” as in let it be a Stuart restoration to the throne.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

Tortoiseshell framed spectacles with a leather case said to have belonged to Lord Lovat. Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat, (1667 – 1747) was chief of clan Fraser, and a Jacobite nicknamed the ‘Old Fox’ for his double-dealings, violent feuds and changes of allegiance. Lovat was convicted of treason for his part in the 1745 Jacobite Rising and was sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. His punishment was commuted to beheading and on 9 April 1747 he was the last person to be publicly executed on Tower Hill, London. Such a crowd gathered for his execution that a stand holding spectators collapsed and killed nine people. Lovat was so amused by the incident that legend has it that this is where the origin of the phrase “laughing your head off” comes from.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

A tooth mounted in a hand-carved ivory frame. The tooth is said to have belonged to Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788). It is very rare and thought to be the only known example of a tooth from the Prince in any museum collection. The tooth is barely worn and would suggest it was probably removed from him as a child. It was gifted to the museum by the Fairfax-Lucy’s of Callart House in 1975.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

A two-sided chair with an embroidered velvet seat said to have been used by Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788). The embroidered inscription reads “August 23 1745 Prince Charles Edward stayed the first night of his march to Inverness with John and Jean Cameron at Fassiefern by Kinlochiel”. Three white feathers in a crown and a white rose are embroidered.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

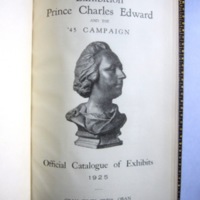

West Highland Museum exhibition catalogue

Description:

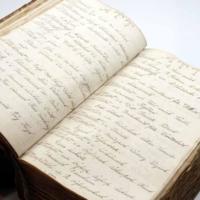

A catalogue for the 1925 West Highland Museum’s exhibition titled “Prince Charles Edward and the ’45 Campaign”. The West Highland Museum was founded in 1922 by a group of local history enthusiasts under the guidance of museum founder, Victor Hodgson. The museum did not have a permanent building until 1926, but ran a series of summer exhibitions as it started its fledgling collection. The 1925 exhibition was the museum’s first major exhibition and significant loans and acquisitions were obtained to make the event possible. This book illustrates how the Jacobites have been at the core of the museum’s collections policy since its inception. This copy of the catalogue belonged to one Duncan Grant and tucked inside is a letter from our founder Victor Hodgson thanking him for sending the packages which arrived safely “which are lying in the bank safe until we arrange the Exhibition”.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

A beautifully carved powder horn with a detailed Celtic design. Powder horns were generally made from horn and used to store gunpowder. This particular object is of great importance as by tradition it belonged to the Gaelic poet, Alasdair MacMhaighstir Alasdair (1700 – 1780). Alasdair lived in Moidart, was the Clan Ranald Bard, and wrote pro-Jacobite poetry. He was among the first to enlist in the 1745 Rising, joining the cause when the Standard was raised at Glenfinnan. He served as a Captain in Clan Ranald’s Regiment throughout the conflict and became Prince Charles Edward Stuart’s (1720 - 1788) Gaelic tutor. He fought at the Battle of Culloden and after the failure of the Rising he went into hiding with his family until 1747.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Image of Alasdair MacMhagister Alastair’s powder horn

Description:

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Image of Alasdair MacMhagister Alastair’s powder horn

Description:

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Image of Alasdair MacMhagister Alastair’s powder horn

Description:

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Image of Alasdair MacMhagister Alastair’s powder horn

Description:

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Image of Alasdair MacMhagister Alastair’s powder horn

Description:

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

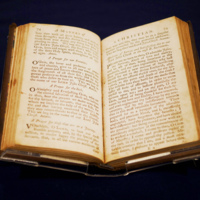

A prayer book titled “A Manual for A Christian”. The prayer book was rebound in the 19th century when the inner and outer case were added. Sadly, no publication information survived this process. The book was gifted to the museum in 2018. It is special because it was said to have been presented by Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788) to the donor’s ancestor on the battlefield at Culloden just before the final conflict of the 1745 Rising. The book has been passed down through the family with each generation documenting its provenance. Inside the cover reads “This book was presented by Prince Charles Stuart to Capt. James MacDonnell of Glengarry. It was transferred by him to his sister Lady Glenbuckett, and afterwards became the property of her son, James Cha.s Gordon.” A letter further supporting the provenance was gifted with the prayer book.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

A large round boulder with a hole bored partially through it. This is a stone with an iconic history. It was originally from Glenfinnan and by tradition is thought to have been used to support the Standard of Prince Charles Edward Stuart when it was raised in August 1745 to signal the beginning of the 1745 Jacobite Rising. The stone remained in situ at Glenfinnan until 1989 when it disappeared from a knoll near the Glenfinnan Monument. It was discovered in an English rockery in 2009 following a BBC programme. The stone is in the care of the museum until a suitable home can be found for it at Glenfinnan.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

This unimposing curved stool made from a tree root has a fascinating history. A label attached to the object states “Stool on which Prince Charlie sat when in hiding in Uist after Culloden.” It was given to the pioneering Victorian folklorist Alexander Carmichael (1832-1912) by Rachel MacDonald, the great granddaughter of Morag MacDonald. Legend has it that three sisters living on a croft on Uist provided food to Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788) one evening when his party passed through the area when they were on the run from Hanoverian troops in 1746. When the sisters realised who their visitor was, they quarrelled as to whom should keep the stool. Morag won the fight and the stool became a treasured family heirloom, until it was gifted to Alexander Carmichael. Part of the Carmichael Collection is now in the museum’s care, while his archive is in the care of Edinburgh University.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Portrait of Clementina Walkinshaw

Description:

This is a very fine portrait of Clementina Walkinshaw (1720–1802), by renowned Scottish artist Allan Ramsay (1713 – 1784). Clementina became the mistress of Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788) in Scotland during the 1745 Rising. They first met in 1746 when Clementina was living with her Uncle at Bannockburn. She was reunited with him in Ghent in 1752 where they rekindled their relationship. In October 1753 Clementina gave birth to Charles’ only daughter, Charlotte. The relationship lasted until 1760 when Clementina and Charlotte fled to a convent, to escape Charles’ increasingly violent and drunken behaviour. Allan Ramsay was the most accomplished Scottish portrait painter of the 18th century and was appointed to the position of King’s painter by George III. In October 1745 he was invited to the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh where produced the only portrait of Prince Charles Edward Stuart known to have been painted in Scotland. The portrait was used as a blueprint for painted and engraved versions, which were employed to promote the Jacobite cause. Examples of miniatures made from the Robert Strange engraving are showcased in this gallery.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Portrait of the Gentle Lochiel

Description:

Portrait of Donald Cameron of Lochiel (1695–1748), ‘The Gentle Lochiel' in a gilt frame. Although this is a copy of a George Chalmers (1720–c.1791) original made 20 years after Lochiel’s death it is an important painting as very few images of the Gentle Lochiel of the 1745 Rising have survived. It is not recorded how the portrait came into the museum’s collection, but it is listed in the catalogue for the West Highland Museum’s 1925 exhibition titled “Prince Charles Edward and the ’45 Campaign” and was possibly gifted to us by Cameron of Lochiel in the 1920s. The Gentle Lochiel played a pivotal role in the 1745 Jacobite Rising. As chief of the powerful Clan Cameron his support for the cause determined whether the campaign could proceed. When the Standard was raised at Glenfinnan in August 1745, Clan Cameron made up two thirds of the Jacobite army. Lochiel led his men throughout the Rising and was injured at the Battle of Culloden on 16 April 1746. He escaped to France with the Prince in 1746 and died in exile in 1748.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Miniatures of Prince Charles Edward Stuart

Description:

Three examples of portraits after the engraving by Robert Strange (1721 -1792). Strange’s engraving was based on the Allan Ramsay (1713 – 1784) portrait of Prince Edward Stuart painted in Edinburgh in 1745. Miniatures like these were copied and widely distributed among Jacobite supporters in the 18th century. The museum has a few examples of different variations of the portrait by Strange. The images are important examples of Jacobite material culture.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Prince Charles Edward Stuart's waistcoat

Description:

A pale green striped silk waistcoat that has been embroidered with rosebuds and silver thread. It is a textile with a fascinating history. The waistcoat once belonged to Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788). It was quite common for Charles to gift his personal belongings to supporters as souvenirs. However, the gifting of his personal clothing is fairly unusual and would have only been bestowed upon his most trusted friends and confidants. In this case the provenance of the waistcoat can be traced. Charles gifted this waistcoat to his doctor, Doctor Irwin, before he left Rome in 1744.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

This is a silver baluster snuff mull with the heraldic arms of Cluny MacPherson set within a foliated scroll formed cartouche. The museum purchased the mull at auction in 2015 specifically for the Jacobite collection. This special object purportedly once belonged to Ewan MacPherson of Cluny the chief of Clan Chattan who led 600 of his clan to fight for the Stuarts in the 1745 Jacobite Rising. After the Rising failed in Spring 1746, the British army burnt Cluny’s house to the ground and he escaped in the Scottish hills living rough, most famously in a small cave known as ‘the cage’ on Ben Alder.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Prince Charles Edward Stuart's trews

Description:

Royal Stewart sett hard tartan trews with integral 'feet'. Traditional trews were not trousers, but long hose which were worn high up to the waist. These are said to have belonged to Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788). The provenance has yet to be fully established, but the trews are believed to date from the 18th century. The trews are special not just because of their connection to the Prince, but because they were one of the earliest objects to come into the museum’s care in 1925. In 2003/4 the trews were loaned to Museo del Tessuto, Prato, Italy for an exhibition.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

This blackthorn walking stick is special for its association with the 1745 Rising. Soon after Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788) first arrived on the Scottish mainland he stayed at Kinlochmoidart House before he proceeded to Glenfinnan where he raised the Standard and signalled the start of the 1745 Rising. This walking stick was carried by Donald Macdonald of Kinlochmoidart (born before 1705 – 1746) at the raising of the Standard on 19 August 1745. He was captured during the rising and executed at Carlisle in October 1746.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

This heavy dirk with a backed blade is made from steel with a wooden hilt decorated with a Celtic knotwork design and brass pins. The dirk is important to the collection because of its connection to Big Duncan Cameron, known in Gaelic as Donnchadh Mor Camshron. At the Battle of Prestonpans in 1745 Duncan was anxious to go forward before the battle and was being restrained by his chief, the Gentle Lochiel. Finally, Duncan broke free and charged across the field followed by other Camerons. The dirk was bequeathed to the museum by his great-great-granddaughter.

Social Media

Player

Metadata

Title:

Description:

This 18th century banner contains the Coat of Arms of MacDonald of Moidart. By tradition this is Clanranald’s Banner which was raised beside the Standard of Prince Charles Edward Stuart at Glenfinnan and was on the battlefield at Culloden. Although, its provenance has not been confirmed. Clan chief Donald MacDonald of Kinlochmoidart (born before 1705 – 1746) fought in the 1745 Rising and was executed at Carlisle in 1746. The banner was originally lodged in the church at Mingarrry in Moidart in the 1920s. It has been restored by the Scottish Conservation Studio and is on long term loan to the museum from the Diocese of Argyll & the Isles.